| |

|

Introduction

Wendell Baker and Civil Rights |

|

|

For five decades Huntsville native Wendell Harold Baker has led the charge for improved race relations as well as political and economic equity. Since the early 1960s, Baker has challenged the local status quo—civic leaders and politicians, educators, the business community, the Black middleclass and church leaders—to make opportunities affordable to people of color and the poor. The son of a biracial businessperson and caring community builder, Baker helped propel the modern-day Civil Rights Movement in Huntsville and Walker County, Texas. Never deterred by his detractors and ambivalent admirers, the eighty-seven-year-old has done more than many national figures for the causes of humanity and social justice. His dismissal from the Huntsville Independent School District (HISD) as instructor and chair of the science department at Sam Houston High School in the early 1960s prompted his emergence as a local community activist. For five decades Huntsville native Wendell Harold Baker has led the charge for improved race relations as well as political and economic equity. Since the early 1960s, Baker has challenged the local status quo—civic leaders and politicians, educators, the business community, the Black middleclass and church leaders—to make opportunities affordable to people of color and the poor. The son of a biracial businessperson and caring community builder, Baker helped propel the modern-day Civil Rights Movement in Huntsville and Walker County, Texas. Never deterred by his detractors and ambivalent admirers, the eighty-seven-year-old has done more than many national figures for the causes of humanity and social justice. His dismissal from the Huntsville Independent School District (HISD) as instructor and chair of the science department at Sam Houston High School in the early 1960s prompted his emergence as a local community activist.

|

The Baker Family

Wendell Baker's Roots in Walker County, Texas |

|

|

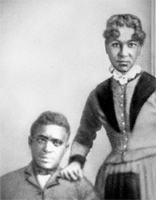

Wendell Harold Baker Sr. was born on November 13, 1922, to Jesse Baker and Fannie Willis Baker on the family’s one-hundred-acre farm in the Cotton Creek community in western Walker County. He was the eighth of ten children born to this union, although his father had an older son from a previous relationship. Although Wendell Baker's parents had loving relationship, their respective backgrounds speak to the brutality of nineteenth-century slavery and racism. Wendell Harold Baker Sr. was born on November 13, 1922, to Jesse Baker and Fannie Willis Baker on the family’s one-hundred-acre farm in the Cotton Creek community in western Walker County. He was the eighth of ten children born to this union, although his father had an older son from a previous relationship. Although Wendell Baker's parents had loving relationship, their respective backgrounds speak to the brutality of nineteenth-century slavery and racism.

Baker’s mother, Fannie, was born in the mid 1890s. She was the granddaughter of a Georgia-born slave named Dinah. Separated from her mother at the age of twelve, Dinah, like her mother, became the victim of rape, ultimately having five children by her master.

Baker’s father, Jesse Baker, was the illegitimate child of Andy Baker, the son of physician Gabriel Baker, the younger brother of James Addison Baker, principle partner of Baker Botts L.L.P. The Baker Brothers moved to Huntsville in the 1840s from Alabama. Gabriel served in the Confederate Army during the Civil War and ultimately had a son, Andy, born in 1866. Andy Baker, who lost his father in 1869, remained in Huntsville, eventually becoming a businessperson. Baker entered into a forbidden sexual liaison with a multiracial African American woman named Emma Curtis. Regrettably, the threat of racial violence prevented the couple from marrying and raising the son. In fact, the threat of racial violence was so great that it motivated Curtis to flee Huntsville and leave her baby with loved ones. Like others across the South, white supremacists, furious over Andy Baker’s decision to support his son and provide him with the family name, took out their anger on Curtis and the African American community in the years that followed Reconstruction. Family friends raised Jesse Baker, and he became a shrewd businessperson with several investments in Walker County, although he had only a rudimentary education. Baker’s father, Jesse Baker, was the illegitimate child of Andy Baker, the son of physician Gabriel Baker, the younger brother of James Addison Baker, principle partner of Baker Botts L.L.P. The Baker Brothers moved to Huntsville in the 1840s from Alabama. Gabriel served in the Confederate Army during the Civil War and ultimately had a son, Andy, born in 1866. Andy Baker, who lost his father in 1869, remained in Huntsville, eventually becoming a businessperson. Baker entered into a forbidden sexual liaison with a multiracial African American woman named Emma Curtis. Regrettably, the threat of racial violence prevented the couple from marrying and raising the son. In fact, the threat of racial violence was so great that it motivated Curtis to flee Huntsville and leave her baby with loved ones. Like others across the South, white supremacists, furious over Andy Baker’s decision to support his son and provide him with the family name, took out their anger on Curtis and the African American community in the years that followed Reconstruction. Family friends raised Jesse Baker, and he became a shrewd businessperson with several investments in Walker County, although he had only a rudimentary education.

Jesse Baker and Fannie Willis fell in love and married in 1909 or 1910, while she was still an adolescent. They bought a 260-acre farm in the Cotton Creek community of western Walker County and were thus landowners, a rarity for people of color at the start of the new century. As such, the Bakers became a source of pride for the larger African American community. Jesse and Fannie Baker not only raised a large family, but also served as a liaison between the Black and white communities. The Black community respected the Bakers; whites tolerated the family while Jesse Baker remained alive. White community leaders had dinner at the Baker home, usually to air racial tensions of some kind. Even during years of uncertainly, the Bakers stood on the forefront of change. Jesse Baker and Fannie Willis fell in love and married in 1909 or 1910, while she was still an adolescent. They bought a 260-acre farm in the Cotton Creek community of western Walker County and were thus landowners, a rarity for people of color at the start of the new century. As such, the Bakers became a source of pride for the larger African American community. Jesse and Fannie Baker not only raised a large family, but also served as a liaison between the Black and white communities. The Black community respected the Bakers; whites tolerated the family while Jesse Baker remained alive. White community leaders had dinner at the Baker home, usually to air racial tensions of some kind. Even during years of uncertainly, the Bakers stood on the forefront of change.

|

The Great Depression

Wendell Baker and his family during the 1930s |

|

|

In 1924, as a farming crisis swept through the nation, the Bakers moved to the Pine Hill community near Huntsville so that their children could attend school. Although the economic hardship caused by the Great Depression certainly affected the community around them, the Bakers persevered. Jesse Baker kept his farm in working order throughout the period, and he made money in other ways as well. He operated a small lumbering firm, raised cattle, smoked and cured meats, and sold milk from his dairy farm. In 1924, as a farming crisis swept through the nation, the Bakers moved to the Pine Hill community near Huntsville so that their children could attend school. Although the economic hardship caused by the Great Depression certainly affected the community around them, the Bakers persevered. Jesse Baker kept his farm in working order throughout the period, and he made money in other ways as well. He operated a small lumbering firm, raised cattle, smoked and cured meats, and sold milk from his dairy farm.

As the Great Depression worsened in the 1930s, African Americans in Texas lost ground economically and socially. The value of Texas farms fell from $3.6 billion to $2.6 billion by 1940. Farm owners and tenants suffered terrible losses. African American sharecroppers in Texas, on average, rarely earned enough to sustain a family. Farm ownership dwindled from 29 percent to 14 percent between 1900 and 1940. The number of African American tenancy even declined as farm owners displaced tens of thousands of sharecroppers and tenants. The number of Afro-American tenants in Texas dwindled from 50,941 to 23,878 between 1935 and 1945. Falling cotton prices, soil depletion, and global competition left Texas farmers in a dire circumstance. The Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) farm allotment program also dispossessed people.

Facing the hardships caused by the Depression, Jesse and Fannie Baker helped others in need. The Bakers had anywhere from seven to ten sharecroppers living on their property, growing cotton. They also provided farm essentials—animals, supplies, and fertilizer—to struggling whites. At a time when 50 percent of southerners lived without indoor plumbing and electricity, Jesse Baker provided electricity to hundreds of western Walker County residents—Black, white, and Latino. He provided his neighbors with cheap, efficient energy. Ultimately, the entire town provided electricity for its residents, years after the Depression ended. Jesse also gave money, plywood, and firewood to surrounding rural schools outside Huntsville. Facing the hardships caused by the Depression, Jesse and Fannie Baker helped others in need. The Bakers had anywhere from seven to ten sharecroppers living on their property, growing cotton. They also provided farm essentials—animals, supplies, and fertilizer—to struggling whites. At a time when 50 percent of southerners lived without indoor plumbing and electricity, Jesse Baker provided electricity to hundreds of western Walker County residents—Black, white, and Latino. He provided his neighbors with cheap, efficient energy. Ultimately, the entire town provided electricity for its residents, years after the Depression ended. Jesse also gave money, plywood, and firewood to surrounding rural schools outside Huntsville.

Fannie, as a member of Parent Teacher Associations (PTA) in the Huntsville area, equally raised hundreds of dollars annually, purchasing school equipment for industrial and domestic science classes, musical instruments, phonographs, kitchen utensils, desks, tables, bookshelves, and projection slides. Fannie and other PTA members also cleaned school grounds and replanted trees on the premises. They also regularly assisted parents, students, and faculty in need.  Equally important, Jesse Baker in the early 1930s persuaded the racist school board to provide Black students with dependable transportation. The Bakers also used their farm as a learning laboratory for students in home economics. Young people learned to cure bacon and sandwich meats; can fruits, vegetables, and preserves; prepare meals; slaughter farm animals; construct barns and sheds; and clean soiled clothes and stitch linen and clothing. Wendell Baker and his siblings, therefore, earned valuable lessons about farming, money management, and community building. Daily they did their chores on the farm, completed their studies, and helped their mother with meals. Equally important, Jesse Baker in the early 1930s persuaded the racist school board to provide Black students with dependable transportation. The Bakers also used their farm as a learning laboratory for students in home economics. Young people learned to cure bacon and sandwich meats; can fruits, vegetables, and preserves; prepare meals; slaughter farm animals; construct barns and sheds; and clean soiled clothes and stitch linen and clothing. Wendell Baker and his siblings, therefore, earned valuable lessons about farming, money management, and community building. Daily they did their chores on the farm, completed their studies, and helped their mother with meals.

The family also encouraged their children to do well in school. In the 1930s, only 10 percent of African Americans finished high school, mostly in urban settings. In rural America, Black families considered school a luxury. Most southern school districts offered African Americans no high school option of any kind. School officials also limited the school year for African Americans, making it easy for families to produce farm commodities. The only high school for African Americans in Walker County, the Samuel Houston Industrial and Training School, a private school established by Samuel Walker Houston, the son of former slave and Reconstruction politician Joshua Houston, provided students a vocational and modest liberal arts education. Still, the struggling school had its limits. The Bakers felt compelled to give their talented son, Wendell, the best education possible. So, Fannie and Jesse Baker sent their son to an urban school in Galveston from 1930 to 1931. The family wanted their gifted son educated in a better school district. He returned to Huntsville, graduating from Sam Houston High School in 1939 with honors. Baker also married briefly and had a daughter, Barbara, who became a science teacher like her father. The family also encouraged their children to do well in school. In the 1930s, only 10 percent of African Americans finished high school, mostly in urban settings. In rural America, Black families considered school a luxury. Most southern school districts offered African Americans no high school option of any kind. School officials also limited the school year for African Americans, making it easy for families to produce farm commodities. The only high school for African Americans in Walker County, the Samuel Houston Industrial and Training School, a private school established by Samuel Walker Houston, the son of former slave and Reconstruction politician Joshua Houston, provided students a vocational and modest liberal arts education. Still, the struggling school had its limits. The Bakers felt compelled to give their talented son, Wendell, the best education possible. So, Fannie and Jesse Baker sent their son to an urban school in Galveston from 1930 to 1931. The family wanted their gifted son educated in a better school district. He returned to Huntsville, graduating from Sam Houston High School in 1939 with honors. Baker also married briefly and had a daughter, Barbara, who became a science teacher like her father.

|

World War II and the Army Medical Corp

Wendell Baker's Service in Pacific Theater |

|

|

In December 1941, Wendell Baker enrolled in Samuel Huston College in Austin, Texas. A science major, Baker believed he could enter graduate or medical school. He sang in the school choir. Unfortunately, World War II delayed his education plans. He had already delayed college for a year in an attempt to raise money for his tuition. For one year, he worked in the school cafeteria at Sam Houston’s Teacher’s College. It frustrated him that he could not attend the college in his hometown with whites. Once again, he would have to put off school, this time because of World War II. With two brothers off at war, Baker had to return home to assist his ailing parents on the family's three-hundred-acre farm. Wendell’s return home benefitted the family in numerous ways. This would soon change, however. In 1944, the United States Army needed new recruits and draftees. Baker shortly after the Battle of the Bulge in central Europe entered the United States Army. He did his basic training at Ft. Sam Houston in San Antonio, and Ft. Louis in Tacoma, Washington. He then completed his technical field assignment training at Camp Crowder, Missouri. Having a gentle and calm demeanor, a certain flare for musical ability, and a 184 IQ, Baker excelled in the segregated United States military. He also married Augusta Lee in 1944 before departing the country for Japan. An exceptional writer, he often wrote love letters for fellow army personnel of all races. He also sung in musical groups, raising money for the war effort. In December 1941, Wendell Baker enrolled in Samuel Huston College in Austin, Texas. A science major, Baker believed he could enter graduate or medical school. He sang in the school choir. Unfortunately, World War II delayed his education plans. He had already delayed college for a year in an attempt to raise money for his tuition. For one year, he worked in the school cafeteria at Sam Houston’s Teacher’s College. It frustrated him that he could not attend the college in his hometown with whites. Once again, he would have to put off school, this time because of World War II. With two brothers off at war, Baker had to return home to assist his ailing parents on the family's three-hundred-acre farm. Wendell’s return home benefitted the family in numerous ways. This would soon change, however. In 1944, the United States Army needed new recruits and draftees. Baker shortly after the Battle of the Bulge in central Europe entered the United States Army. He did his basic training at Ft. Sam Houston in San Antonio, and Ft. Louis in Tacoma, Washington. He then completed his technical field assignment training at Camp Crowder, Missouri. Having a gentle and calm demeanor, a certain flare for musical ability, and a 184 IQ, Baker excelled in the segregated United States military. He also married Augusta Lee in 1944 before departing the country for Japan. An exceptional writer, he often wrote love letters for fellow army personnel of all races. He also sung in musical groups, raising money for the war effort.

Baker, while a private, protested the war the best way he could. A conscientious objector, Baker refused to care a rifle. His argument resonated with millions of African Americans, including the more than one million serving their country during World War II. He could not see himself fighting in a war for a country that routinely discriminated against African Americans. A supporter o “Double V”, he espoused not only the dismantling of the Nazi and militarist Japanese war machines, but also hoped for an end to racial discrimination. An estimated twelve thousand conscientious objectors served in World War II, mostly with the Civilian Public Service. Baker, too, remained in the army and performed essential duties for the war effort, regardless of his political views. Although a defiant Wendell Baker made money for the United States Military performed invaluable services to the army, he did not always see the fruits of his labor rewarded in the racist, segregated armed services. His outfit eventually left Seattle, Washington, for Yokohama, Japan. While the army listed on paper Baker and fellow shipmate Ebenezer Bush, a retired dentist in Los Angeles, as laborers with an all-Black unit, the two men, largely because of their exceptional test scores, worked for the Army Medical Corp (now the Army Medical Department of the United States Army). Both worked in the port dispensary as medical personnel. Baker, a surgical technician assisted physicians with surgical procedures. Baker also oversaw the administration units and immunization services. Regrettably, Jim Crow dictates prevented them from earning what their white peers earned. Nor did the army promote them as they had the white medical staffers they supervised and trained. They entered the army as privates and left the army as privates. The experience and social contacts, nevertheless, made the racist ordeal worthwhile. Baker, while a private, protested the war the best way he could. A conscientious objector, Baker refused to care a rifle. His argument resonated with millions of African Americans, including the more than one million serving their country during World War II. He could not see himself fighting in a war for a country that routinely discriminated against African Americans. A supporter o “Double V”, he espoused not only the dismantling of the Nazi and militarist Japanese war machines, but also hoped for an end to racial discrimination. An estimated twelve thousand conscientious objectors served in World War II, mostly with the Civilian Public Service. Baker, too, remained in the army and performed essential duties for the war effort, regardless of his political views. Although a defiant Wendell Baker made money for the United States Military performed invaluable services to the army, he did not always see the fruits of his labor rewarded in the racist, segregated armed services. His outfit eventually left Seattle, Washington, for Yokohama, Japan. While the army listed on paper Baker and fellow shipmate Ebenezer Bush, a retired dentist in Los Angeles, as laborers with an all-Black unit, the two men, largely because of their exceptional test scores, worked for the Army Medical Corp (now the Army Medical Department of the United States Army). Both worked in the port dispensary as medical personnel. Baker, a surgical technician assisted physicians with surgical procedures. Baker also oversaw the administration units and immunization services. Regrettably, Jim Crow dictates prevented them from earning what their white peers earned. Nor did the army promote them as they had the white medical staffers they supervised and trained. They entered the army as privates and left the army as privates. The experience and social contacts, nevertheless, made the racist ordeal worthwhile.

|

The College Years

Texas State University for Negroes and Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity |

|

|

Baker entered Texas State University for Negroes (TSUN) in the fall of 1947. The war hero benefited from the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 (GI Bill), which provided veterans with a free college education. He left off where he started and continued majoring in chemistry. During his two years in college, he worked part-time to support his new wife and son but found time for extracurricular activities. He loved singing and joined the glee club. He also established the campus’s first Alpha Phi Alpha chapter. The first of nine Black Greek-lettered fraternal societies on college campuses, seven college students established Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity on the campus of Cornell University in 1906. One of the seven founders, social worker Eugene K. Jones, later served as the first executive secretary of the National Urban League and Federal Council on Negro Affairs (The Black Cabinet). A charter member of TSUN’s Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Wendell H. Baker put forth an agenda that included academic excellence, civic leadership and civil rights. His hectic schedule did not hurt his grades. He graduated with honors in 1949. With his heart set on medical school, he left Houston and returned to Huntsville to help his mother care for the family job while at the same time save money. Baker entered Texas State University for Negroes (TSUN) in the fall of 1947. The war hero benefited from the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 (GI Bill), which provided veterans with a free college education. He left off where he started and continued majoring in chemistry. During his two years in college, he worked part-time to support his new wife and son but found time for extracurricular activities. He loved singing and joined the glee club. He also established the campus’s first Alpha Phi Alpha chapter. The first of nine Black Greek-lettered fraternal societies on college campuses, seven college students established Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity on the campus of Cornell University in 1906. One of the seven founders, social worker Eugene K. Jones, later served as the first executive secretary of the National Urban League and Federal Council on Negro Affairs (The Black Cabinet). A charter member of TSUN’s Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Wendell H. Baker put forth an agenda that included academic excellence, civic leadership and civil rights. His hectic schedule did not hurt his grades. He graduated with honors in 1949. With his heart set on medical school, he left Houston and returned to Huntsville to help his mother care for the family job while at the same time save money.

|

From Educator to Engineer

Wendell Baker, Huntsville Independent Schools, and the Goodyear Tire Company in Beaumont |

|

|

Wendell Baker dreamed of entering Meharry Medical School. After securing his undergraduate degree at Texas Southern University in 1949, Baker, who now possessed a chemistry degree, decided a brief career in teaching would provide him with the economic means to both support his fledgling family and save money to cover tuition and fees for his first few years of medical school. By the early 1950s, however, it became clear that medical school would never happen. His family of seven needed him fulltime; at the same time, his students enjoyed his energy and needed him as well. The chairperson of the Sam Houston High School science division, Baker taught physical science, biology, chemistry, and physics. His science went on fieldtrips across the state, while his glee clubbers traveled across the country and performed at numerous events. Often, he negotiated with his white peers who had the best science equipment and books. While illegal, white peers sometimes gave him unused equipment and textbooks for his classes. Baker’s determination propelled a number of students into math and science as career choices. Only his firing in 1962 for building his ranch-style brick home near several new white subdivisions near his parents’ property ended his passionate career as a devoted HISD educator. In addition, a weekend disc jockey, he lost his second job as well. He took work substitute teaching in nearby communities and did odd jobs to make ends meet. Eventually, however, he found his way back to permanent employment. Wendell Baker dreamed of entering Meharry Medical School. After securing his undergraduate degree at Texas Southern University in 1949, Baker, who now possessed a chemistry degree, decided a brief career in teaching would provide him with the economic means to both support his fledgling family and save money to cover tuition and fees for his first few years of medical school. By the early 1950s, however, it became clear that medical school would never happen. His family of seven needed him fulltime; at the same time, his students enjoyed his energy and needed him as well. The chairperson of the Sam Houston High School science division, Baker taught physical science, biology, chemistry, and physics. His science went on fieldtrips across the state, while his glee clubbers traveled across the country and performed at numerous events. Often, he negotiated with his white peers who had the best science equipment and books. While illegal, white peers sometimes gave him unused equipment and textbooks for his classes. Baker’s determination propelled a number of students into math and science as career choices. Only his firing in 1962 for building his ranch-style brick home near several new white subdivisions near his parents’ property ended his passionate career as a devoted HISD educator. In addition, a weekend disc jockey, he lost his second job as well. He took work substitute teaching in nearby communities and did odd jobs to make ends meet. Eventually, however, he found his way back to permanent employment.

Often dubbed “the Jackie Robinson of the Golden Triangle,” Baker began working at the Goodyear Tire Company in Beaumont in 1962. In fact, Baker became the first African American technical professional when Goodyear hired him as a quality-control specialist, ultimately promoting him to chemical engineer. Baker’s responsibilities included the testing of machinery and chemical plants that helped convert raw materials into the processed chemicals the company used in the development of synthetic rubber. Baker worked at the company for twenty-two years, from 1962 to 1984. His transformation from fired schoolteacher to chemical engineer not only tripled his salary, but also prompted his catapult into local activism.

|

Voting Rights Activist

Wendell Baker and the Walker County Voters League |

|

|

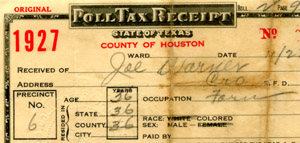

Wendell Baker, a scientist with the Goodyear Tire Co., now found himself in a position to help his community. In 1965, he began pressing the Black community about civil rights. His major concern addressed voting rights. On August 6, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act. The act banned discriminatory practices in the area of voting rights. While the Fifteen Amendment outlawed discrimination that prevented United States citizens from voting in local, statewide, and national elections, southern states formed a number of loopholes that made voting difficult for African Americans. In Texas, for example, the White Democratic Primary (1923) prohibited African Americans from voting in Texas primary elections. Baker, who carried a little weight in the community as an engineering professional, met with a number of clergy leaders in hopes of convincing individuals to pay their poll taxes and vote. Not surprisingly, most ministers resisted. Black ministers, along with other leaders, felt direct confrontation at the polls could precipitate backlashes. Baker carried his message to ministers in numerous counties surrounding Walker County. The response was principally the same. He and his wife Augusta decided on another method. They decided the family would reach out the community in another way. They would pay the poll taxes for hundreds of African-American residents. Appreciative and determined, Walker County Blacks decisively went the polls and voted out of office a racist sheriff who held captive people of color for decades. Wendell Baker, a scientist with the Goodyear Tire Co., now found himself in a position to help his community. In 1965, he began pressing the Black community about civil rights. His major concern addressed voting rights. On August 6, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act. The act banned discriminatory practices in the area of voting rights. While the Fifteen Amendment outlawed discrimination that prevented United States citizens from voting in local, statewide, and national elections, southern states formed a number of loopholes that made voting difficult for African Americans. In Texas, for example, the White Democratic Primary (1923) prohibited African Americans from voting in Texas primary elections. Baker, who carried a little weight in the community as an engineering professional, met with a number of clergy leaders in hopes of convincing individuals to pay their poll taxes and vote. Not surprisingly, most ministers resisted. Black ministers, along with other leaders, felt direct confrontation at the polls could precipitate backlashes. Baker carried his message to ministers in numerous counties surrounding Walker County. The response was principally the same. He and his wife Augusta decided on another method. They decided the family would reach out the community in another way. They would pay the poll taxes for hundreds of African-American residents. Appreciative and determined, Walker County Blacks decisively went the polls and voted out of office a racist sheriff who held captive people of color for decades.

|

School Desegregation

Wendell Baker and the Public Schools of Huntsville, Texas |

|

|

The Walker County Voter’s League also put a plan into motion to force school desegregation. The organization met with numerous groups, from educators to ministers, in hope of strategizing a workable course of action. As in other instances, middle-class Blacks felt uneasy challenging the status quo. They actually scoffed at Baker and demanded that he end his actions before risking the jobs of thousands. In all earnestness, people had good reason to fear reprisals. Huntsville Blacks felt more vulnerable compared to those living in major U.S. cities. The modern Civil Rights Movement forced the world to observe the contradictions of United States democracy. Activists risked their jobs, homes, livelihood, and lives in an effort to transform their world. Baker nevertheless considered the accommodating actions of his neighbors and acquaintances ludicrous. He turned to working-class African Americans. In January 1964, Wendell H. Baker presented his desegregation plan to HISD school superintendent Mance Park. Park, the same individual responsible for Baker’s firing several years earlier, detested his former employee. He initially refused Baker’s request. A recalcitrant Superintendent Park and school board eventually supported a “freedom of choice” plan that favored transferring a select number of high-performing Black elementary students to the White elementary school. Little Janet Smithers, a second grader whose parents volunteered for the school district’s first “freedom of choice” desegregation plan, became the first African-American student to attend school with white students the following year. Not surprising, whites made her feel unwelcome. Her painful and humiliating experience did in fact precipitate the complete desegregation of the district by the late 1960s. Truthfully, the board had to comply with the Brown ruling or risk losing millions of dollars in federal aid. By 1965, a growing number of East Texas school districts desegregated their schools. The defiant school district finally agreed to desegregate its schools in 1968 by way of “freedom of choice,” instead of forced compliance, fourteen years after the Brown ruling and four years following the emotional and tumultuous entry of Miss Janet Smither. The Walker County Voter’s League also put a plan into motion to force school desegregation. The organization met with numerous groups, from educators to ministers, in hope of strategizing a workable course of action. As in other instances, middle-class Blacks felt uneasy challenging the status quo. They actually scoffed at Baker and demanded that he end his actions before risking the jobs of thousands. In all earnestness, people had good reason to fear reprisals. Huntsville Blacks felt more vulnerable compared to those living in major U.S. cities. The modern Civil Rights Movement forced the world to observe the contradictions of United States democracy. Activists risked their jobs, homes, livelihood, and lives in an effort to transform their world. Baker nevertheless considered the accommodating actions of his neighbors and acquaintances ludicrous. He turned to working-class African Americans. In January 1964, Wendell H. Baker presented his desegregation plan to HISD school superintendent Mance Park. Park, the same individual responsible for Baker’s firing several years earlier, detested his former employee. He initially refused Baker’s request. A recalcitrant Superintendent Park and school board eventually supported a “freedom of choice” plan that favored transferring a select number of high-performing Black elementary students to the White elementary school. Little Janet Smithers, a second grader whose parents volunteered for the school district’s first “freedom of choice” desegregation plan, became the first African-American student to attend school with white students the following year. Not surprising, whites made her feel unwelcome. Her painful and humiliating experience did in fact precipitate the complete desegregation of the district by the late 1960s. Truthfully, the board had to comply with the Brown ruling or risk losing millions of dollars in federal aid. By 1965, a growing number of East Texas school districts desegregated their schools. The defiant school district finally agreed to desegregate its schools in 1968 by way of “freedom of choice,” instead of forced compliance, fourteen years after the Brown ruling and four years following the emotional and tumultuous entry of Miss Janet Smither.

In July 1964, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act. Hailed as the “legislative” equivalent of the Brown decision, the act transformed the South. City officials in Huntsville had no other choice but to comply or face criminal charges. In 1950, the Supreme Court ordered the University of Texas to enroll Heman Sweatt, a mail carrier from Houston, at its law school. Fifteen years later, however, Sam Houston State Teacher’s College remained off limits to African Americans. Wendell Baker and the Walker County Voter’s League once again instigated compliance. This time the group selected students to enroll in classes at Sam Houston State Teacher’s College (SHSC). The first student, Annie Lee Kizzie, unsuccessfully applied for admissions. The college registrar informed the student that the school did not admit non-White students. Of course, this was not entirely true. Historian Amilcar Shabazz, in his award-winning Advancing Democracy (2004), argues that public colleges and university across the state, including Sam Houston State, regularly admitted East Indian, Japanese, Chinese, American Indian, and Latino students. Yes, Jim Crow exclusion occasionally shut varying groups of non-Whites out of the college admissions process; however, for the most part, non-Black students of color had greater accessibility to Texas schools than Blacks. Baker, the Voter’s League, and a new ally, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), brought to SHSC a new Black applicant. This time a Willis schoolteacher, Maxine Haywood, transferred to the teacher’s college. At first, the admissions office accepted her application. However, once officials at the registrar’s office recognized Haywood’s Prairie View A. & M. College transcript, the registrar quickly rescinded her transfer. Baker, along with members of the voter’s League and NAACP immediately filed a suit with the federal district court. The news media made an embarrassing spectacle of the ordeal, especially for the governor, who at the time was out of the state but contacted. Sources suggest that he ordered the board to overturn the school’s segregation policy and admit Black students. In 1964, the board of regents at SHSC agreed to comply with the civil rights act and ordered the immediate desegregation of its school. John Patrick, a young man who graduated with honors at Sam Houston High School, became the first African American student to attend the teacher’s college. At the time of his graduation in 1969, the university had hundreds more enrolled in its varying degree plans. In July 1964, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act. Hailed as the “legislative” equivalent of the Brown decision, the act transformed the South. City officials in Huntsville had no other choice but to comply or face criminal charges. In 1950, the Supreme Court ordered the University of Texas to enroll Heman Sweatt, a mail carrier from Houston, at its law school. Fifteen years later, however, Sam Houston State Teacher’s College remained off limits to African Americans. Wendell Baker and the Walker County Voter’s League once again instigated compliance. This time the group selected students to enroll in classes at Sam Houston State Teacher’s College (SHSC). The first student, Annie Lee Kizzie, unsuccessfully applied for admissions. The college registrar informed the student that the school did not admit non-White students. Of course, this was not entirely true. Historian Amilcar Shabazz, in his award-winning Advancing Democracy (2004), argues that public colleges and university across the state, including Sam Houston State, regularly admitted East Indian, Japanese, Chinese, American Indian, and Latino students. Yes, Jim Crow exclusion occasionally shut varying groups of non-Whites out of the college admissions process; however, for the most part, non-Black students of color had greater accessibility to Texas schools than Blacks. Baker, the Voter’s League, and a new ally, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), brought to SHSC a new Black applicant. This time a Willis schoolteacher, Maxine Haywood, transferred to the teacher’s college. At first, the admissions office accepted her application. However, once officials at the registrar’s office recognized Haywood’s Prairie View A. & M. College transcript, the registrar quickly rescinded her transfer. Baker, along with members of the voter’s League and NAACP immediately filed a suit with the federal district court. The news media made an embarrassing spectacle of the ordeal, especially for the governor, who at the time was out of the state but contacted. Sources suggest that he ordered the board to overturn the school’s segregation policy and admit Black students. In 1964, the board of regents at SHSC agreed to comply with the civil rights act and ordered the immediate desegregation of its school. John Patrick, a young man who graduated with honors at Sam Houston High School, became the first African American student to attend the teacher’s college. At the time of his graduation in 1969, the university had hundreds more enrolled in its varying degree plans.

|

HA-YOU

Wendell Baker and the Youth Movement in Huntsville, Texas |

|

|

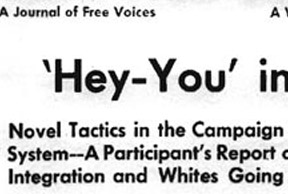

Baker, who expressed excitement about the board’s decision, focused on broadening the national Civil Rights Movement in Huntsville. During the summers of 1964 and 1965, Baker traveled across the South to witness firsthand the strategies, tactics, discussions, and concerns of grassroots and national civil rights leaders. Baker, without question, understood that young people in particular had a right to charter their own destiny and challenge the status quo for access and equity. He especially hoped his participation in the various workshops over the past few years would help motivate greater passion and zeal among Huntsville’s future leaders, the young. Once again, an energized Baker pushed for community involvement. Although older and middle-class Blacks considered Baker a rabble-rouser and troublemaker, young people answered his call. Anxious Sam Houston High School students in 1964 and 1965 pushed for the desegregation of their city’s schools, restaurants, theater, public swimming pool, library, courthouse, shopping centers, and drugstores. They also demanded equal access to good-paying jobs. Motivated by an AFL-CIO meeting in Austin that addressed Freedom Summer in Mississippi, the Huntsville students decided to formulate their own direct protest tactics and forcibly desegregate their city. The students returned to Huntsville, requested the aid of Rev. Oliver and Wendell Baker, and set out to make history. Baker, who expressed excitement about the board’s decision, focused on broadening the national Civil Rights Movement in Huntsville. During the summers of 1964 and 1965, Baker traveled across the South to witness firsthand the strategies, tactics, discussions, and concerns of grassroots and national civil rights leaders. Baker, without question, understood that young people in particular had a right to charter their own destiny and challenge the status quo for access and equity. He especially hoped his participation in the various workshops over the past few years would help motivate greater passion and zeal among Huntsville’s future leaders, the young. Once again, an energized Baker pushed for community involvement. Although older and middle-class Blacks considered Baker a rabble-rouser and troublemaker, young people answered his call. Anxious Sam Houston High School students in 1964 and 1965 pushed for the desegregation of their city’s schools, restaurants, theater, public swimming pool, library, courthouse, shopping centers, and drugstores. They also demanded equal access to good-paying jobs. Motivated by an AFL-CIO meeting in Austin that addressed Freedom Summer in Mississippi, the Huntsville students decided to formulate their own direct protest tactics and forcibly desegregate their city. The students returned to Huntsville, requested the aid of Rev. Oliver and Wendell Baker, and set out to make history.

The students and their adult supporters—including Baker—in July 1965 formed the SCLC-affiliated Huntsville Action for Youth (Ha-You, pronounced Hey-You). Beginning on Saturday, July 18, Ha-You activists—Baker, members of the Negro Chamber of Commerce, students, White students and activists from other communities, and ministers—picketed outside business establishments that refused to cater to Blacks, including the Life Theater, boutiques, restaurants, and drug stores. Tempers flared whites threw the activists when the activists out of the Texan Café. The protests spread to the Walker County Courthouse on the second and third days. When police made arrests, many local Blacks blamed Baker. They understandably feared for the safety of their children. Even Augusta Baker, Wendell’s wife, worried about their children’s safety in the wake of potential interracial violence and police brutality, and in the end, forbade their involvement in the local demonstrations. Baker believed, nevertheless, that direct protest in Huntsville could and would lead to fundamental and quick changes. Within two weeks, the controversial protests led to the desegregation of the entire City of Huntsville.

|

An Incomplete Victory

Wendell Baker and the Continuing Fight for Civil Rights |

|

|

The success of both the Walker County Voter’s League and Ha-You Movement led to a number of far-reaching changes for Blacks. SHSC enrolled its first African-American students by 1965. The police department in the mid-1960s hired its first Black officers since Reconstruction. The Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) also began hiring Black correctional officers and secretarial staffers. The school system finally equalized teacher’s salaries. African-American clerical staff also worked in city and county offices. Whites served Black customers in business establishments throughout the city. In the 1970s, SHSU students involved in the antiwar movement sought Baker’s advice. Baker also worked with students to lift the alcoholic ban in the county limits. From voting apathy to charges of discrimination in local government offices, Baker continues to challenge his community on matters pertaining to fairness and equity. The success of both the Walker County Voter’s League and Ha-You Movement led to a number of far-reaching changes for Blacks. SHSC enrolled its first African-American students by 1965. The police department in the mid-1960s hired its first Black officers since Reconstruction. The Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) also began hiring Black correctional officers and secretarial staffers. The school system finally equalized teacher’s salaries. African-American clerical staff also worked in city and county offices. Whites served Black customers in business establishments throughout the city. In the 1970s, SHSU students involved in the antiwar movement sought Baker’s advice. Baker also worked with students to lift the alcoholic ban in the county limits. From voting apathy to charges of discrimination in local government offices, Baker continues to challenge his community on matters pertaining to fairness and equity.

|

|

|

|

|