| |

|

| |

click an image for more information |

Introduction

The Sawmill Industry in East Texas |

|

|

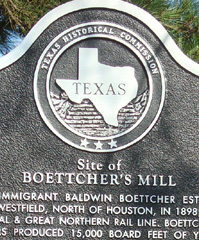

The sawmill industry has been a major component of the East Texas economy since the mid-nineteenth century. As large cities such as Houston grew, so did their appetite for lumber. Mills sprang up in boom town fashion and as soon as the trees were harvested, the mill would be disassembled and moved to a new location. Following this pattern, Boettcher's Mill was established in 1929 one mile from Huntsville's town square, just outside the city limits. It was a community of lumber mill workers and their families who had relocated when the trees ran out at the Westfield Mill in Montgomery County, just south of Walker County. Rather than quit the business as many small operators were doing at that time, Edward Boettcher purchased a tract of trees and moved his sawmill. In its heyday, Ed Boettcher's mill was the single largest privately owned business in Walker County, employing over 500 workers. The surrounding village that sprung up included Mexican, black and white families and, in time, would prove to be a unique and vibrant community. For the most part, histories of East Texas have overlooked it, perhaps because of the long shadow cast by the state's penitentiary system, located in Huntsville and earning it the nickname, “Prison City” or perhaps, because on the surface it looked like every other East Texas sawmill community. However, upon closer inspection and with a little digging, it appears that the community at Boettcher's Mill was unique in a variety of ways and merits more attention than historians have previously given it. The sawmill industry has been a major component of the East Texas economy since the mid-nineteenth century. As large cities such as Houston grew, so did their appetite for lumber. Mills sprang up in boom town fashion and as soon as the trees were harvested, the mill would be disassembled and moved to a new location. Following this pattern, Boettcher's Mill was established in 1929 one mile from Huntsville's town square, just outside the city limits. It was a community of lumber mill workers and their families who had relocated when the trees ran out at the Westfield Mill in Montgomery County, just south of Walker County. Rather than quit the business as many small operators were doing at that time, Edward Boettcher purchased a tract of trees and moved his sawmill. In its heyday, Ed Boettcher's mill was the single largest privately owned business in Walker County, employing over 500 workers. The surrounding village that sprung up included Mexican, black and white families and, in time, would prove to be a unique and vibrant community. For the most part, histories of East Texas have overlooked it, perhaps because of the long shadow cast by the state's penitentiary system, located in Huntsville and earning it the nickname, “Prison City” or perhaps, because on the surface it looked like every other East Texas sawmill community. However, upon closer inspection and with a little digging, it appears that the community at Boettcher's Mill was unique in a variety of ways and merits more attention than historians have previously given it.

The residents of Boettcher's Mill, particularly the Mexicans, were quite distinctive compared to other saw mill residents in East Texas. First, many of the residents had migrated north after the Mexican Revolution of 1910. Coming from Monterrey, the second largest city in Mexico and located in the northern province of Nuevo Leon, these families -- including the de Soto, Garcia, Hernandez, Juarez, Martinez, Mellado, Montoya, Moreno, Ramirez, Rodriguez, and Zamora families -- experienced both political and economic hardship. Monterrey has been compared to Chicago -- a great northern industrial city that rivaled its national capitol in terms of economic and political influence. Perhaps because it was so economically important to the country, the revolutionary leader Pancho Villa was known to terrorize the local population around Monterrey. Powerful industrialists resisted efforts of the new revolutionary government on the issue of labor reform, shutting down factories and refusing to implement new laws that protected labor. The steel mills closed, many workers lost their jobs and as a result headed north across the Mexican-U.S. border. Many of the Mexican American families who finally ended up in Boettcher's Mill outside of Huntsville, Texas, were a part of this northern migration. The residents of Boettcher's Mill, particularly the Mexicans, were quite distinctive compared to other saw mill residents in East Texas. First, many of the residents had migrated north after the Mexican Revolution of 1910. Coming from Monterrey, the second largest city in Mexico and located in the northern province of Nuevo Leon, these families -- including the de Soto, Garcia, Hernandez, Juarez, Martinez, Mellado, Montoya, Moreno, Ramirez, Rodriguez, and Zamora families -- experienced both political and economic hardship. Monterrey has been compared to Chicago -- a great northern industrial city that rivaled its national capitol in terms of economic and political influence. Perhaps because it was so economically important to the country, the revolutionary leader Pancho Villa was known to terrorize the local population around Monterrey. Powerful industrialists resisted efforts of the new revolutionary government on the issue of labor reform, shutting down factories and refusing to implement new laws that protected labor. The steel mills closed, many workers lost their jobs and as a result headed north across the Mexican-U.S. border. Many of the Mexican American families who finally ended up in Boettcher's Mill outside of Huntsville, Texas, were a part of this northern migration.

|

Crossings: Coming to America

Migration and the Origins of Boettcher's Mill |

|

|

The story of Boettcher's Mill actually begins with the story of two waves of migration to Texas, one from Germany in the late nineteenth century and another from Mexico in the early twentieth century. Baldwin Boettcher arrived in Texas in 1887 from the region of Saxony in Germany. He went through immigration processing in Galveston, which was the second busiest immigration station in the United States, trailing only Ellis Island in New York City. The story of Boettcher's Mill actually begins with the story of two waves of migration to Texas, one from Germany in the late nineteenth century and another from Mexico in the early twentieth century. Baldwin Boettcher arrived in Texas in 1887 from the region of Saxony in Germany. He went through immigration processing in Galveston, which was the second busiest immigration station in the United States, trailing only Ellis Island in New York City.

Within a couple of years he had purchased timbered land and set up a sawmill in Westfield, just north-west of Houston. Baldwin established his mill at the height of the sawmill boom in East Texas and he made a very successful living as a result of investing in the lumber industry. Eventually, his timberland and mill holdings were passed on to his son, Edward. Today, the Baldwin Boettcher Library, located on Aldine Westfield Road in Humble, sits on two acres of the original Westfield Mill which were donated by his descendants to the Harris County Library system.

Elzora Boettcher (1875-1957), Baldwin’s wife, played a crucial role at the mill as well. When Baldwin died in 1912, Elzora oversaw mill operations in Westfield while her son, Edward, who was 19 at the time, attended a business college in Louisiana for one year, after which he returned to run the mill. Even after Edward’s homecoming, Elzora continued to take a very active interest in the family business. She went to the mill every day to check on the operations and people at the site. After completing some correspondence courses through the Chicago School of Nursing, she also carried a little metal case of medical supplies, which she used to attend to the health of the residents. She even served as a midwife on occasion. Indeed, Elzora became a very prominent presence in Huntsville, such that when she passed, the local paper referred to her as "Mother Boettcher."

The story of the Mexican families who wound up in Boettcher's Mill in 1929 began about a decade earlier with Dionisio Martinez. In the political and economic upheaval of early-twentieth century Mexico, Dionisio's father left the family in search of work and was not seen again. Dionisio, born in 1891 and being the eldest son, took over the role of patriarch of the family at the age of 12. The family lived just outside of Monterrey, and some of the male family members worked in the steel mills. But the mills closed and the men found themselves without work. At the same time, the revolutionary leader Pancho Villa was wreaking havoc in the area. One of his generals drafted Dionisio into the army after the young man successfully delivered some ransom gold by wagon to Pancho Villa.

Not wishing to be caught up in the uncertainty of revolution, Dionisio and his siblings made the decision, as many other residents of the northern province of Nuevo Leon did, to move north to the United States. Led by Dionisio, the family crossed the border at Laredo. There, they paid a small immigration fee and were then free to settle in the U.S. They made their way to Montgomery County where Dionisio found work with the railroad and his brothers found work at Groggins Mill. Eventually, they moved to Westfield to work for Edward Boettcher in his sawmill. Not wishing to be caught up in the uncertainty of revolution, Dionisio and his siblings made the decision, as many other residents of the northern province of Nuevo Leon did, to move north to the United States. Led by Dionisio, the family crossed the border at Laredo. There, they paid a small immigration fee and were then free to settle in the U.S. They made their way to Montgomery County where Dionisio found work with the railroad and his brothers found work at Groggins Mill. Eventually, they moved to Westfield to work for Edward Boettcher in his sawmill.

|

The Road North

Moving the Mill and Its Town from Westfield to Walker County |

|

|

Though the bonanza era for East Texas lumber mills ended in 1917, Ed Boettcher continued his father's sawmill operation. But the mill at Westfield finally had to close when the trees gave out. In some respect, it was a planned obsolescence. Some mills were destroyed by fire, others by economic downturn. In the case of Westfield, the workers had done their work and done it well; there were simply no trees left to log. The trees had been turned into lumber, and then it was time to move on. In anticipation of this, Ed Boettcher had purchased timber land east of Huntsville in Walker County, just north of Montgomery County. The employees disassembled the mill piece by piece, labeling parts for later reassembling. They loaded the pieces on the train to be hauled north to just outside of Huntsville. The houses were also disassembled, packed up and then moved by wagon. Most families had livestock, so the men walked the animals some sixty miles to Huntsville along an old road that paralleled the highway. Though the bonanza era for East Texas lumber mills ended in 1917, Ed Boettcher continued his father's sawmill operation. But the mill at Westfield finally had to close when the trees gave out. In some respect, it was a planned obsolescence. Some mills were destroyed by fire, others by economic downturn. In the case of Westfield, the workers had done their work and done it well; there were simply no trees left to log. The trees had been turned into lumber, and then it was time to move on. In anticipation of this, Ed Boettcher had purchased timber land east of Huntsville in Walker County, just north of Montgomery County. The employees disassembled the mill piece by piece, labeling parts for later reassembling. They loaded the pieces on the train to be hauled north to just outside of Huntsville. The houses were also disassembled, packed up and then moved by wagon. Most families had livestock, so the men walked the animals some sixty miles to Huntsville along an old road that paralleled the highway.

By the time the families of the workers had arrived, Mr. Boettcher had already had a communal well dug and established where each of the groups would live. At a time and in a country where segregation was the norm, sawmill communities adhered to an unspoken hierarchy that was manifested in the way the town was laid out. The old segregated way of life was even reflected in the language because the Mexican and black sections of Boettcher's Mill were referred to as “quarters.” White mill workers, who typically held the clerical and managerial jobs, were the highest paid and lived conveniently close to the mill office and commissary. At Boettcher's Mill, this meant that the Anglos lived on top of the hill. The Mexican families lived below the Anglos. The black workers' families lived in close proximity to each other at the bottom of the hill. Though the men often worked physically close together during the day, come whistle time they walked home to their respective parts of the neighborhood. To some degree, this was self-segregation at Boettcher's Mill since many of the Mexican families were related, spoke Spanish in their homes, and had worked together for a number of years while at the Westfield Mill. By the time the families of the workers had arrived, Mr. Boettcher had already had a communal well dug and established where each of the groups would live. At a time and in a country where segregation was the norm, sawmill communities adhered to an unspoken hierarchy that was manifested in the way the town was laid out. The old segregated way of life was even reflected in the language because the Mexican and black sections of Boettcher's Mill were referred to as “quarters.” White mill workers, who typically held the clerical and managerial jobs, were the highest paid and lived conveniently close to the mill office and commissary. At Boettcher's Mill, this meant that the Anglos lived on top of the hill. The Mexican families lived below the Anglos. The black workers' families lived in close proximity to each other at the bottom of the hill. Though the men often worked physically close together during the day, come whistle time they walked home to their respective parts of the neighborhood. To some degree, this was self-segregation at Boettcher's Mill since many of the Mexican families were related, spoke Spanish in their homes, and had worked together for a number of years while at the Westfield Mill.

|

Working at Boettcher's Mill

Labor and Meaning in Walker County |

|

|

Because it was a permanent and good-sized mill that even boasted a spur railroad line with its own locomotive, Boettcher's Mill operated all three stages of lumber production: cutting the timber, milling it, and then delivering it to retail operations. Then within each of these stages there were numerous jobs with varying degrees of skill required. Those who have been interviewed tend to agree that Ed Boettcher did not always have preset notions about race when it came to job assignments. The woodsmen, the men who worked in the forest, were roughly 2/3 white and 1/3 black. For many of them, logging was a way of life and by the 1910s, they were second generation loggers. The actual tree-cutting was some of the toughest work to be done and in the Texas climate with its mild winters, it could be done year-round as long as the economy permitted. On the other hand, in the summertime the men worked in temperatures of 100 degrees and in mosquito-infested, swampy areas teeming with cotton mouths and copperheads. The work was continuous, exhausting, and seven times more dangerous than other manufacturing industry jobs. Because it was a permanent and good-sized mill that even boasted a spur railroad line with its own locomotive, Boettcher's Mill operated all three stages of lumber production: cutting the timber, milling it, and then delivering it to retail operations. Then within each of these stages there were numerous jobs with varying degrees of skill required. Those who have been interviewed tend to agree that Ed Boettcher did not always have preset notions about race when it came to job assignments. The woodsmen, the men who worked in the forest, were roughly 2/3 white and 1/3 black. For many of them, logging was a way of life and by the 1910s, they were second generation loggers. The actual tree-cutting was some of the toughest work to be done and in the Texas climate with its mild winters, it could be done year-round as long as the economy permitted. On the other hand, in the summertime the men worked in temperatures of 100 degrees and in mosquito-infested, swampy areas teeming with cotton mouths and copperheads. The work was continuous, exhausting, and seven times more dangerous than other manufacturing industry jobs.

Getting the trees to the mill required several steps. The trees were first felled with double-handled saws. Once the tree was felled, branches were removed and they were cut into 16 or 20 foot lengths. Felling and then “skidding,” or the gathering up of the logs, could be very dangerous. A log twenty feet long and 18" in diameter weighed one ton, so mules were used to drag the log to the railroad car. The mules were kept in the log camp and cared for by someone who knew how to handle them. The logs would then be loaded onto the wagon while the “top loader,” or a man on top guided the logs into place. This was a particularly dangerous job because if a log shifted, he may be knocked off or suffer a crushing injury. Once the wagon or truck was successfully loaded, the logs were hauled to the mill. The railroad used to haul the finish lumber off was built by the “steel gang,” or special crew formed to lay the railroad ties and steel track. Getting the trees to the mill required several steps. The trees were first felled with double-handled saws. Once the tree was felled, branches were removed and they were cut into 16 or 20 foot lengths. Felling and then “skidding,” or the gathering up of the logs, could be very dangerous. A log twenty feet long and 18" in diameter weighed one ton, so mules were used to drag the log to the railroad car. The mules were kept in the log camp and cared for by someone who knew how to handle them. The logs would then be loaded onto the wagon while the “top loader,” or a man on top guided the logs into place. This was a particularly dangerous job because if a log shifted, he may be knocked off or suffer a crushing injury. Once the wagon or truck was successfully loaded, the logs were hauled to the mill. The railroad used to haul the finish lumber off was built by the “steel gang,” or special crew formed to lay the railroad ties and steel track.

Boettcher's Mill dominated the landscape with its large millpond, the towering mill, and the constantly burning fire that produced thick black smoke. The millpond was the first part of the mill to be constructed and this is where the fresh cut timber was unloaded. The pond served to clean the logs after they had been dragged through the dirt to keep the saws from being dulled or damaged. The pond also protected them from insects because though pine logs float, most of the log was below the surface of the water. Boettcher's Mill dominated the landscape with its large millpond, the towering mill, and the constantly burning fire that produced thick black smoke. The millpond was the first part of the mill to be constructed and this is where the fresh cut timber was unloaded. The pond served to clean the logs after they had been dragged through the dirt to keep the saws from being dulled or damaged. The pond also protected them from insects because though pine logs float, most of the log was below the surface of the water.

The logs would then be brought to the log deck, or the first floor of the mill, and then brought up and positioned by the lead sawyer for the bandsaw where the mill work would begin in earnest. Large planks were cut and then sent to either the “tail sawyer” who was responsible for sending them to a gang saw where identical boards were cut at once, or to the “edger-man” who determining the quality of the planks and further cutting into standard sized boards. These jobs were highly skilled and required lots of experience. They were also higher paid and typically held by white men. However, at Boettcher's Mill they were often held by Hispanic men. From there, merchantable boards and waste alike ended up in the “bear pit” where one man, usually black, quickly sorted it and tried not to get covered up. Finally, the “trimmer” cut the boards into lengths depending on their quality.

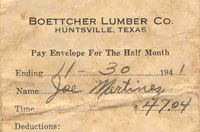

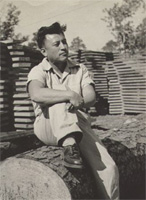

Many other jobs were integral to the sawmill operation besides the actual mill work. Saw blades were sharpened and reinstalled a few times every day. Power to run the mill in the form of boilers, engines and flywheels had to be maintained. Ed Boettcher began to use trucks, rather than mules and wagons, to haul the logs into the mill and as a result, needed mechanics on site to maintain his fleet of vehicles. The vehicle repair shop became the realm of the Mexican employees because Dionisio,s brother, Jose Martinez, was a good mechanic and was chosen to oversee that part of the mill operation. He ordered books in Spanish to learn more about how to maintain the trucks and studied them in the evenings. He became such a trusted employee that Ed Boettcher once gave him enough cash to take ten employees to Louisiana, purchase ten new trucks and then have them driven back to the mill. Many other jobs were integral to the sawmill operation besides the actual mill work. Saw blades were sharpened and reinstalled a few times every day. Power to run the mill in the form of boilers, engines and flywheels had to be maintained. Ed Boettcher began to use trucks, rather than mules and wagons, to haul the logs into the mill and as a result, needed mechanics on site to maintain his fleet of vehicles. The vehicle repair shop became the realm of the Mexican employees because Dionisio,s brother, Jose Martinez, was a good mechanic and was chosen to oversee that part of the mill operation. He ordered books in Spanish to learn more about how to maintain the trucks and studied them in the evenings. He became such a trusted employee that Ed Boettcher once gave him enough cash to take ten employees to Louisiana, purchase ten new trucks and then have them driven back to the mill.

Boettcher's Mill lacked the ‘boom atmosphere' that was present in earlier mill towns in part because it was located close to Huntsville and had already existed previously in Westfield. It was a quiet place that did not experience much trouble. The mill had been in existence in Walker County for nearly ten years when the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 ordered that the minimum wage be followed by all companies engaging in interstate trade. Because Ed Boettcher sold his lumber beyond the state of Texas, he had to make a decision: either pay his workers more or stop shipping lumber beyond the boundaries of Texas. Employees' salaries comprised one of the mill's largest proportions of costs, and increasing that cost may have put the mill out of business. He made the decision to stop shipping his lumber beyond state lines and to not increase his employees' pay. So the mill stayed in business, though the employees lost out. Even though the mill was relocated to Huntsville at a very economically precarious time (1929), ultimately the business was managed well and its employees and their families endured during the Great Depression.

Despite Ed Boettcher's skillful management, the workers were not complacent about the low wages they received. Though an 8-hour work day had been established shortly after the minimum wage, Ed and then his son, Clint, routinely did not adhere to the 8-hour day until the 1960s. They also worked a six-day week including Saturdays. Dissatisfied with their situation, 38 employees asked their supervisor to talk to Clint Boettcher, which he did. Boettcher came outside his office to speak to the disgruntled group and reminded them of all the advantages that employment at his mill afforded them: low-cost housing, credit at the commissary, and no utility bills to pay. Unless they were prepared to move, there were not many other jobs to be found in the area either. The men stayed, though they did not get the 50-cent raise they had hoped for; instead, they received a 10-cent raise. It is interesting to note that the Brotherhood of Timber Workers, the union for sawmill workers, never reached Boettcher's Mill. Despite Ed Boettcher's skillful management, the workers were not complacent about the low wages they received. Though an 8-hour work day had been established shortly after the minimum wage, Ed and then his son, Clint, routinely did not adhere to the 8-hour day until the 1960s. They also worked a six-day week including Saturdays. Dissatisfied with their situation, 38 employees asked their supervisor to talk to Clint Boettcher, which he did. Boettcher came outside his office to speak to the disgruntled group and reminded them of all the advantages that employment at his mill afforded them: low-cost housing, credit at the commissary, and no utility bills to pay. Unless they were prepared to move, there were not many other jobs to be found in the area either. The men stayed, though they did not get the 50-cent raise they had hoped for; instead, they received a 10-cent raise. It is interesting to note that the Brotherhood of Timber Workers, the union for sawmill workers, never reached Boettcher's Mill.

|

Living at Boettcher's Mill

A New Community Takes Root in Walker County |

|

|

Life at Boettcher's Mill was similar to many small southern towns in the early half of the twentieth century. While the men worked in the mill, their wives worked maintaining their homes and caring for their children. The houses at Boettcher's Mill were typical of sawmill communities, being square and containing four rooms: a living room, kitchen/dining room, and two bedrooms. The floors were made of uncovered wood; one resident remembers sweeping the floor and then finding the biggest crack to push the dirt through. There was a wood stove in the kitchen, but that was the only source of heat during the winter. Vivian de Soto, Jr., recalled that as a new recruit in the U.S. Army, he was unimpressed by threats from drill sergeants who promised unimaginable hardships; he'd grown up in a house without heat and felt prepared for anything after that. Later in the 1950s, many of these homes had linoleum flooring put down over the wood and would eventually be dry-walled. These improvements would help to insulate the houses against both cold and heat. There was an outhouse in the backyard and water was drawn from the community spigot in the beginning. Eventually, many of the men dug wells in between houses so that two houses shared a well and cold water was provided inside the house. Life at Boettcher's Mill was similar to many small southern towns in the early half of the twentieth century. While the men worked in the mill, their wives worked maintaining their homes and caring for their children. The houses at Boettcher's Mill were typical of sawmill communities, being square and containing four rooms: a living room, kitchen/dining room, and two bedrooms. The floors were made of uncovered wood; one resident remembers sweeping the floor and then finding the biggest crack to push the dirt through. There was a wood stove in the kitchen, but that was the only source of heat during the winter. Vivian de Soto, Jr., recalled that as a new recruit in the U.S. Army, he was unimpressed by threats from drill sergeants who promised unimaginable hardships; he'd grown up in a house without heat and felt prepared for anything after that. Later in the 1950s, many of these homes had linoleum flooring put down over the wood and would eventually be dry-walled. These improvements would help to insulate the houses against both cold and heat. There was an outhouse in the backyard and water was drawn from the community spigot in the beginning. Eventually, many of the men dug wells in between houses so that two houses shared a well and cold water was provided inside the house.

The houses in each section -- white, Mexican and black -- differed in some ways. Housing for whites included porches and were the first to be plumbed and electrified. The Mexican homes had porches as well and utilities such as electricity were installed by the men. African American houses lacked porches and were more often in disrepair. Ed Boettcher provided the lumber for the homes but then left it up to each family to make any improvements. The appearance of the homes reflected the level of pay that the head of household received at the mill. Those who were paid least spent their time off from the mill earning extra income. For example, scrap wood was free to employees so some sold it as firewood to residents of Huntsville to supplement the family income. “Free” time for some was better spent in earning needed income than maintaining the appearance of their houses.

For the Mexican families, it was typical to have a large garden and to keep livestock that often included a milk cow and chickens. The men rose early to work in the garden for an hour before heading for the mill. What was not eaten fresh from the garden the women canned and dried for later consumption. The women also typically made the family's clothing. If there was time, an enterprising mother supplemented the family income by sewing for others, or trading tamales for medical treatment, for example. Mexican children came directly home from school to help with the chores. The boys often found work that paid such as working in the store-- sweeping, cleaning, and running errands– while others collected cast-off wood and sold it as firewood in town, or sold ice for iceboxes. The girls tended to help their mothers in the home, either with the cooking, laundry, or cleaning. These gendered patterns of work kept daughters safe at home and away from contact with strangers outside the neighborhood while the boys were more exposed to the broader context of Huntsville. For the Mexican families, it was typical to have a large garden and to keep livestock that often included a milk cow and chickens. The men rose early to work in the garden for an hour before heading for the mill. What was not eaten fresh from the garden the women canned and dried for later consumption. The women also typically made the family's clothing. If there was time, an enterprising mother supplemented the family income by sewing for others, or trading tamales for medical treatment, for example. Mexican children came directly home from school to help with the chores. The boys often found work that paid such as working in the store-- sweeping, cleaning, and running errands– while others collected cast-off wood and sold it as firewood in town, or sold ice for iceboxes. The girls tended to help their mothers in the home, either with the cooking, laundry, or cleaning. These gendered patterns of work kept daughters safe at home and away from contact with strangers outside the neighborhood while the boys were more exposed to the broader context of Huntsville.

What could not be made or produced at home was purchased at the mill commissary, a typical feature of any mill town. While it was customary for commissary prices to run between 10 to 15 percent higher than prices elsewhere, Ed Boettcher's decision to build the commissary cannot be attributed solely to a bottom line. Those interviewed believe that the store was built in large part for the convenience of his workers and many former residents insist that the pricing was fair and the quality of goods decent. Rather than walk to town, (generally, residents at the mill could not afford automobiles) where some were refused service because of their race, the store provided anything the mill families might need. Some families did go into town by wagon on Saturdays to shop, but the commissary was handy for day-to-day purchases. In an age before refrigeration, it was convenient to be able to purchase perishable items daily. School supplies, clothing, hats, and shoes also filled the shelves.

At the Westfield mill in the 1910s and 20s, the employees had been paid in tokens that could only be used in the company store there -- a common practice in most mill towns and it was not uncommon for workers to be in debt to the Boettcher's Mill store. However, Boettcher did abide by a 1914 law that dictated that employees be paid twice monthly and in cash. The only time he deviated from this was during the worst of the Depression when cash was hard to come by. In those years, Ed Boettcher sometimes had to resort to using script, but he used it sporadically and only temporarily. Ed Boettcher was particular about the quality of meat he consumed, so as one resident pointed out the meat available was sometimes superior to what could be purchased in town and consequently, townspeople were sometimes known to shop at Boettcher's store instead. At one point, Huntsville business owners complained that mill families were not shopping in their stores so Ed Boettcher paid his employees in two dollar bills. Shortly thereafter, those two dollar bills were circulating all over town, proving the point that mill workers were contributing to the local economy.

Ed Boettcher not only supplied the lumber for houses and the commissary, but for churches as well because religion was an important part of life in the community. However, to assume that the Mexican families living in Boettcher's Mill were all Catholics would be a mistake. The Martinezes had been raised in Mexico as Catholics, but Dionisio had become disillusioned with the extravagant lifestyles of some of the Catholic clergymen. While living and working at the mill in Westfield he had become friendly with a Mexican man who invited him to his church. The sermons were in Spanish, as was the promotional literature. As it turns out, the church was a Baptist one of the fundamental persuasion. Dionisio was swayed by the teachings of this branch of Christianity and in time, the Mexican families at Boettcher's Mill became strong adherents of the Baptist faith. Sundays became the time for large family gatherings at the Martinez house after church. Dionisio's son was dispatched in the family truck to pick up family friends who lived thirty miles away in Madisonville but wanted to attend the “Mexican” Baptist church at Boettcher's Mill. The family would stay for dinner, and then be driven home at the end of the day. Ed Boettcher not only supplied the lumber for houses and the commissary, but for churches as well because religion was an important part of life in the community. However, to assume that the Mexican families living in Boettcher's Mill were all Catholics would be a mistake. The Martinezes had been raised in Mexico as Catholics, but Dionisio had become disillusioned with the extravagant lifestyles of some of the Catholic clergymen. While living and working at the mill in Westfield he had become friendly with a Mexican man who invited him to his church. The sermons were in Spanish, as was the promotional literature. As it turns out, the church was a Baptist one of the fundamental persuasion. Dionisio was swayed by the teachings of this branch of Christianity and in time, the Mexican families at Boettcher's Mill became strong adherents of the Baptist faith. Sundays became the time for large family gatherings at the Martinez house after church. Dionisio's son was dispatched in the family truck to pick up family friends who lived thirty miles away in Madisonville but wanted to attend the “Mexican” Baptist church at Boettcher's Mill. The family would stay for dinner, and then be driven home at the end of the day.

Many of the permanent mill towns were known to be “Christian” towns, and this was indeed the case for Boettcher's Mill. For example, Sam Montoya moved away for a time but returned later because he wanted to raise his children in what he believed to be a “Christian community.” Religiosity may have been encouraged by mill owners, in part, to help keep order both at work and at home. For the Mexican American community at Boettcher's Mill, the church not only helped bind unrelated families together, but it also hastened the process of assimilation. Joining a Protestant church in predominantly Protestant East Texas made any preconceived notions about Catholicism a moot point. Many of the permanent mill towns were known to be “Christian” towns, and this was indeed the case for Boettcher's Mill. For example, Sam Montoya moved away for a time but returned later because he wanted to raise his children in what he believed to be a “Christian community.” Religiosity may have been encouraged by mill owners, in part, to help keep order both at work and at home. For the Mexican American community at Boettcher's Mill, the church not only helped bind unrelated families together, but it also hastened the process of assimilation. Joining a Protestant church in predominantly Protestant East Texas made any preconceived notions about Catholicism a moot point.

One building that Ed Boettcher did not provide lumber for was a school. Rather than build a school on site as many mill owners did, the children at Boettcher's attended Huntsville schools. To educate children at the mill would have been a costly endeavor because separate schools would have been expected—one for white children and one for black and Mexican children. Two schools would have required the hiring of two teachers, adding further costs. Educating employees' children was common practice in mill towns, in part because it gave the mill owner more control over the residents by limiting outside influence. Boettcher simply may have wanted to cut costs and save money. But an agreement was worked out between the city of Huntsville and Ed Boettcher and the children of Boettcher's Mill were then sent to Huntsville schools. Boettcher also persuaded Huntsville school authorities to allow the Mexican children to attend the white rather than the black school, and as history has shown, this decision ensured that they would receive a better education. They would also have access to middle and high school; mill town schools typically only provided education through the sixth grade and so in yet another way, the children of Boettcher's Mill had greater educational opportunities than children growing up in other mill towns.

The children who were educated in the Huntsville school system beginning in the 1930s remember days before bilingual education and desegregation. The Mexican children learned Spanish in their homes, but bilingual education was a concept of the future. Children were expected to speak English immediately and were punished if they spoke in their native Spanish. When there was time for the boys to play football after school, Mexican and white children played together, but black children never joined in those games. While Ed Boettcher may not have had the intention of accelerating the assimilation process for his Mexican workers' children, that was the exact effect it had and in some ways may account for the successes of many of these children as they grew into adulthood. The decision not to build schools meant that the children were exposed to a broader cultural experience.

Overall, the Mexican children who grew up in Boettcher's Mill have found memories of it. As one former resident said “We were poor; we just didn't know we were poor.” Though their fathers were paid low wages even compared to other East Texas mill towns, they were never without food or a roof over their heads even during the Depression years. They had the advantage of being brought up in a close knit community of extended family ties, united by church, culture, ethnicity and class, while at the same time being forced into an accelerated process of assimilation through the public school system. |

Sawmill Barrio

Community and the Development of Hispanic Culture in an East Texas Mill Town |

|

|

The Hispanic community that developed at Boettcher's Mill contributed to the multifaceted culture of Huntsville as the children grew to adulthood and began to leave the mill. Perhaps the first real taste of Mexican culture came to the area when Zenobia Martinez, wife of Jose, opened the first Mexican restaurant in Walker County. Jose had managed to save $4000 from 1929 to 1944, including his wages and the contributions from his sons. With that money he purchased two acres with a house and store on Highway 19. Zenobia opened the restaurant in 1957 with only twelve dollars, twelve plates, and four tables. On the first day she made more money than Jose had made in a month when working at the mill. Jose, who was retired by 1957, had been skeptical about opening the restaurant but changed his mind once he realized the money that was to be made. According to his daughter, the success of his wife's restaurant caused him to realize how poorly paid he had been his entire life. The Hispanic community that developed at Boettcher's Mill contributed to the multifaceted culture of Huntsville as the children grew to adulthood and began to leave the mill. Perhaps the first real taste of Mexican culture came to the area when Zenobia Martinez, wife of Jose, opened the first Mexican restaurant in Walker County. Jose had managed to save $4000 from 1929 to 1944, including his wages and the contributions from his sons. With that money he purchased two acres with a house and store on Highway 19. Zenobia opened the restaurant in 1957 with only twelve dollars, twelve plates, and four tables. On the first day she made more money than Jose had made in a month when working at the mill. Jose, who was retired by 1957, had been skeptical about opening the restaurant but changed his mind once he realized the money that was to be made. According to his daughter, the success of his wife's restaurant caused him to realize how poorly paid he had been his entire life.

Assimilation came in other ways for the Boettcher's Mill Hispanics. Jose had been encouraged by Dr. Goodrich, the doctor who had served the mill community, to join the Shreiner's. Over time, Jose reached the highest level within the organization and routinely traveled to Houston to participate in the groups's activities. Edward Boettcher along with Amos Gates, a long-time county judge, also helped the Mexican residents to gain citizenship. The men, who learned English while at work, passed the citizenship exam the first tine they took it, but the women tended not to and it would take longer for them to do so. World War II offered another way for the sons of the original Mexican settlers to demonstrate their loyalty to America for several served during that war. |

End of a Mill Town: End of an Era

Boettcher's Mill and the Mill Town Come to an End |

|

|

Boettcher's Mill retained much of the old ways of mill town life well into the 1960s. Mill wages remained well under the state average and though many of the mill homes had been sold to the residents, no major improvements had been made to the neighborhood. Upon Ed Boettcher's death in 1967, his son Clinton took over the mill operation at a time when it was operating at about 25% of its peak capacity. But the mill was still producing plenty of smoke and those who grew up there remember the huge “mountains” of sawdust that continually smoldered and burned. The women had learned that only on certain days and at certain times was it safe to hang laundry out to dry without it becoming covered in soot. As the nation was learning about the negative health effects of poor air quality, several residents approached Clint Boettcher to see if something could be done to minimize the pollution. Eventually, the Environmental Protection Agency was contacted and representatives came to investigate the mill. A hearing was held and the result was that the mill would have to comply with new federal guidelines or cease operation. Clint Boettcher decided that the improvements mandated by the court were too costly. So after forty years the mill finally closed in 1969. Boettcher's Mill retained much of the old ways of mill town life well into the 1960s. Mill wages remained well under the state average and though many of the mill homes had been sold to the residents, no major improvements had been made to the neighborhood. Upon Ed Boettcher's death in 1967, his son Clinton took over the mill operation at a time when it was operating at about 25% of its peak capacity. But the mill was still producing plenty of smoke and those who grew up there remember the huge “mountains” of sawdust that continually smoldered and burned. The women had learned that only on certain days and at certain times was it safe to hang laundry out to dry without it becoming covered in soot. As the nation was learning about the negative health effects of poor air quality, several residents approached Clint Boettcher to see if something could be done to minimize the pollution. Eventually, the Environmental Protection Agency was contacted and representatives came to investigate the mill. A hearing was held and the result was that the mill would have to comply with new federal guidelines or cease operation. Clint Boettcher decided that the improvements mandated by the court were too costly. So after forty years the mill finally closed in 1969.

Though the mill closed, the company houses continued to be occupied by former employees and their families. Over time, residents had purchased the houses from the Boettcher family. But the area occupied a rather anachronistic place in the history of Walker County. The city of Huntsville had grown around it and city fathers had intentionally allowed that to happen. The area had none of the services provided by the city such as sewers, water and garbage pick-up and to provide them would have cost the city more than it would redeem in taxes should the area be annexed. These conditions persisted in the mill town until the early 1960s because it was a way for Ed Boettcher to keep the cost of rent down.

But the impoverished neighborhood was not an attractive target for annexation in the eyes of Huntsville's city fathers. In 1984, fifteen years after the closing of the mill, the city finally annexed Boettcher's Mill and the following year the city received a $500,000 grant to renovate the area. Some of the company houses still stand today and although not elegant, serve as testament to the quality lumber produced at Boettcher's Mill. Today, the area contains a park fittingly named “Boettcher's Mill Park,” although in 2005 the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) tried to convince the Huntsville City Council to rename it after a Hispanic figure who had never lived nor worked at the mill. In the end, the Hispanics who had grown up at the mill persuaded the council to maintain their history. Reflecting the experiences and desires of the first Mexican families who settled in Huntsville, the park retains its original name: “Boettcher's Mill Park.” But the impoverished neighborhood was not an attractive target for annexation in the eyes of Huntsville's city fathers. In 1984, fifteen years after the closing of the mill, the city finally annexed Boettcher's Mill and the following year the city received a $500,000 grant to renovate the area. Some of the company houses still stand today and although not elegant, serve as testament to the quality lumber produced at Boettcher's Mill. Today, the area contains a park fittingly named “Boettcher's Mill Park,” although in 2005 the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) tried to convince the Huntsville City Council to rename it after a Hispanic figure who had never lived nor worked at the mill. In the end, the Hispanics who had grown up at the mill persuaded the council to maintain their history. Reflecting the experiences and desires of the first Mexican families who settled in Huntsville, the park retains its original name: “Boettcher's Mill Park.”

|

|

|

|

|